For the embedded systems engineer, the mantra has long been “optimize and deploy.” You architect a highly efficient, tightly constrained Deep Neural Network (DNN) model, deploy it to the edge, a drone, an industrial sensor, a medical device, and expect it to perform reliably for a decade. But what happens when the operational environment shifts, new failure modes appear, or user behavior evolves?

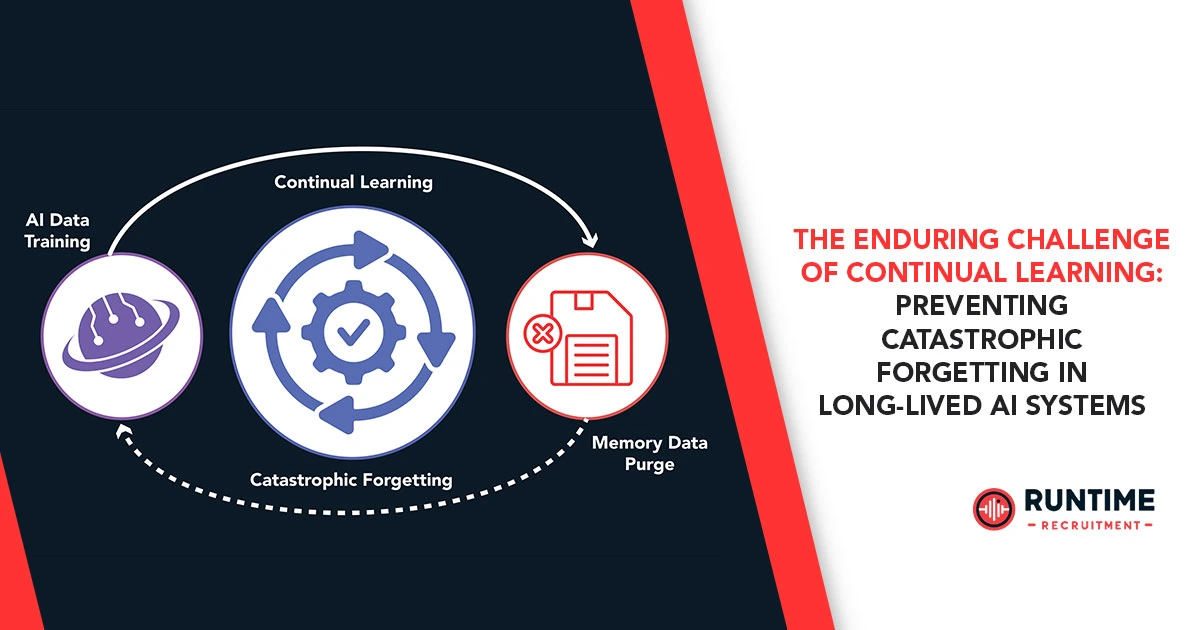

In the current paradigm, the answer is often a costly, over-the-air (OTA) update: a complete model re-training and redeployment cycle, consuming significant bandwidth, power, and flash endurance. The future of true Edge AI, however, demands Continual Learning (CL), the ability for a model to adapt to a non-stationary data stream without needing to be retired and retrained from scratch.

This ambition immediately confronts a core vulnerability of neural networks: Catastrophic Forgetting (CF). CF is the rapid, complete erasure of previously learned knowledge when a network is trained on new tasks or data. For an embedded system, this isn’t a mere performance drop; it’s a mission-critical failure. A surveillance drone that learns to identify a new threat type, only to forget how to recognize a basic vehicle, is a system that has become a liability.

This article delves into the unique, resource-constrained challenges of combating CF on the edge and explores the algorithmic and architectural co-design solutions that are essential for long-lived, truly autonomous embedded AI.

The Severity of Catastrophic Forgetting in the Embedded Context

Catastrophic forgetting is a profound challenge rooted in the mechanics of Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) within over-parameterized models. When a DNN learns a new task (Task B), its weights $(\theta)$ are updated to minimize the loss on the new data, $L_B(\theta)$. The vast majority of the network’s parameters are shared between Task A and Task B. As the optimization for $L_B(\theta)$ aggressively pushes the shared weights in a new direction, the weights that encoded the knowledge of Task A, the global optima of the previous loss function $L_A(\theta)$—are violently overwritten.

$$\theta_{t+1} = \theta_t – \eta \cdot \nabla L_{B}(\theta_t)$$

The magnitude of this gradient-induced interference is what defines the “catastrophe.”

Unique Constraints of Edge Deployment

On a cloud server, one can simply run a full batch of all historical and new data (Joint Training), solving the problem trivially at the cost of massive computational overhead. The embedded engineer does not have this luxury. The constraints that define the embedded CL problem are:

| Constraint | Embedded System Impact | Algorithmic Consequence |

| Limited RAM/Flash | Strict limit on historical data storage (the Replay Buffer). | Forcing the use of tiny, highly compressed exemplar sets or generative models. |

| Limited Compute/Power | On-device training must be minimal, often running on a low-power NPU/DSP. | Disqualifies computationally heavy methods like Gradient Episodic Memory (GEM) or deep structural modification. |

| Non-Stationary Data | Real-world data stream is sequential (online) and often task-free (no explicit task boundary). | Requires continuous, one-pass learning rather than batch-based, task-incremental learning. |

| Functional Safety (ISO 26262/etc.) | Forgetting a previously validated safety state is unacceptable. | Demands measurable, auditable metrics for knowledge retention (Forgetting Rate). |

The challenge is to achieve high plasticity (rapidly learn new features) while maintaining high stability (protecting old knowledge) under severe Size, Weight, and Area, and Power (SWaP) budgets. This is the ultimate Stability-Plasticity Tradeoff.

The Embedded CL Toolkit: Three Pillars of Mitigation

The modern CL landscape offers three primary families of techniques to combat CF, each presenting a distinct set of trade-offs for the embedded developer.

1. Regularization-Based Methods (Synaptic Consolidation)

Inspired by the concept of synaptic consolidation in the human brain, these methods protect important parameters by adding a penalty term to the new task’s loss function. The foundational technique is Elastic Weight Consolidation (EWC).

The EWC Mechanism

EWC penalizes the change in weights $(\theta)$ proportional to their importance to the previous task(s). The new loss function $L_{new}$ for task $T_B$ becomes:

$$L_{new}(\theta) = L_B(\theta) + \sum_{i} \frac{\lambda}{2} F_i (\theta_i – \theta_{A,i}^*)^2$$

Where:

- $\theta_{A,i}^*$ is the optimal weight for parameter $i$ after learning Task A.

- $\lambda$ is the importance hyperparameter (stability-plasticity tradeoff).

- $F_i$ is the Fisher Information Matrix (FIM) diagonal for weight $i$.

The FIM is the core of EWC. It estimates the curvature of the loss function $L_A(\theta)$ at the optimal weight $\theta_{A}^*$, quantifying how sensitive the previous loss is to a change in $\theta_i$. A large $F_i$ means the model relies heavily on $\theta_i$ for Task A, and changes to it are heavily penalized.

Embedded Implementation: The FIM Approximation

Calculating the full FIM for a large network is computationally infeasible and memory-prohibitive. For embedded systems, we must rely on extreme approximations:

- Online EWC: Instead of calculating a full FIM after a complete task, the FIM is incrementally updated with each new sample/mini-batch. This distributes the computational cost and avoids a large, sudden spike in processing.

- Diagonal Approximation: The true FIM is a dense matrix. Embedded EWC universally uses the diagonal elements, $F_i$, reducing the required memory from $O(|\theta|^2)$ to $O(|\theta|)$.

- Decoupled Gradient Computation: Since the FIM calculation requires second-order derivatives (or the squared expectation of first-order derivatives), the embedded platform must be capable of efficiently computing and storing two sets of information: the standard backpropagation gradients and the squared gradients for the FIM update.

Pro: Low memory footprint, as no previous data samples need to be stored (Data-Free CL).

Con: Computationally intensive FIM calculation and potentially less effective when new tasks significantly interfere with core feature representations.

2. Rehearsal/Replay-Based Methods (Experience Consolidation)

Rehearsal methods are the most effective for mitigating CF. They store a small subset of data from previous tasks, the Exemplar Set or Replay Buffer, and interleave the training on this old data with the new data. This effectively transforms an online sequential learning problem into a local, miniature multitask learning problem.

Memory Management: The Embedded Bottleneck

The effectiveness of Rehearsal is directly proportional to the size and quality of the replay buffer, $P$. Since the embedded memory budget $K$ is tight, the strategy shifts from how much to store to what to store.

- Reservoir Sampling: The simplest method, which randomly keeps samples. Effective for instance-incremental learning.

- Herding (iCaRL): A more sophisticated method where samples are selected by finding the ones whose feature representation mean (in the last layer’s embedding space) is closest to the class mean of the previous task. This ensures the exemplar set is highly representative of the old decision boundary, offering the greatest knowledge value per stored byte. This introduces a computational cost for feature extraction and mean calculation that must be factored into the on-device update budget.

- Generative Replay: To eliminate the need for storing private or raw data, a small Generative Model (e.g., a lightweight Autoencoder or GAN) can be trained to synthesize “pseudo-data” from previous tasks. While this offloads the memory cost, it adds the computational cost of maintaining and sampling from a secondary generative network. This is often only viable on high-end edge AI SoCs with dedicated accelerators.

Optimization for Power: Sequential Rehearsal

Instead of mixing old and new batches simultaneously (Concurrent Rehearsal), which increases batch size and power draw, Sequential Rehearsal can be used: update on the new task first, then run a short “consolidation” step on the replay buffer. Recent research suggests Sequential Rehearsal performs better when tasks are highly dissimilar, offering a critical power optimization for embedded engineers.

3. Parameter and Architectural Isolation Methods

These methods aim to avoid weight overlap entirely by dedicating specific network resources to new tasks.

- Learning Without Forgetting (LwF): This is a distillation-based method. When learning Task B, the old network is frozen and used as a teacher. The new network is trained not only on the Task B ground truth, but also to mimic the Task A output logits of the teacher network. This encourages the new network’s weights to maintain the existing Task A output behavior. Crucially, the old network does not need to be stored in its entirety, only the final layer’s outputs (logits) are required during the new training phase.

- Dynamic Architectures: Techniques like Progressive Neural Networks (PNNs) or Rep-Nets freeze the core backbone and add Task-Specific Parameters (TSPs) or a small parallel network for new knowledge. This offers near-perfect CF prevention, but at the cost of increasing the overall model size and memory footprint with every new task, a significant drawback for embedded flash storage. Modern approaches focus on Prompt-Based CL, where only small, lightweight “prompts” are learned and inserted into the frozen backbone, offering a far more memory-efficient version of structural plasticity.

Practical Implementation: Metrics and Low-Level Co-Design

Implementing CL requires more than just picking an algorithm; it demands a full-stack co-design approach to ensure the system remains resource-efficient and reliable over its lifecycle.

The Need for Embedded CL Metrics

The standard CL metrics must be adapted for SWaP constraints:

- Average Accuracy (ACC): The mean accuracy across all tasks seen so far.

- Forgetting Rate ($F_{T}$): The most critical embedded metric. It quantifies the performance degradation on previous tasks. For task $T_i$ trained at time $t_i$ and evaluated at $t_{final}$:

$$F_{T_i} = \max_{j < k} \left( A_{i, j} \right) – A_{i, k}$$

Where $A_{i, j}$ is the accuracy of task $i$ after training task $j$. A low, predictable $F_T$ is a prerequisite for any safety-critical deployment.

- Computational Overhead (Ops/Update): Measures the total floating-point operations (FLOPs) required to incorporate one new sample/batch. This determines the power profile and the maximum frequency of on-device updates.

- Memory Overhead (Bytes/Update): The flash/RAM used for storing Exemplar Set data or FIM matrices. A typical design point must target less than 1MB of non-volatile memory for rehearsal storage on many constrained microcontrollers.

Hardware/Software Co-Design for CL

The embedded CL engine cannot be treated as a pure software layer.

- Memory Hierarchy Optimization:

- Replay Buffer Placement: Crucial replay buffer samples should reside in high-endurance, non-volatile memory (e.g., dedicated MRAM/PRAM blocks on the chip or high-speed, low-power SLC NAND) to minimize write amplification and power-intensive fetches from slower flash storage.

- In-Memory Computing (IMC): Emerging IMC/CIM architectures are inherently suited for CL. Training involves extensive Matrix-Vector Multiplications (MVMs). By performing these operations directly within the memory array (e.g., using resistive RAM), the massive power cost of data movement between the core and external memory is virtually eliminated, making on-device backpropagation far more feasible. This is the future of truly low-power, persistent on-device learning.

- Quantization and Sparsity:

- Post-Training Quantization (PTQ) vs. Quantization-Aware Training (QAT): The CL update loop must integrate a quantization strategy (e.g., 8-bit or 4-bit INT) to reduce the memory footprint of the weights and activations. Quantization-Aware Fine-Tuning is often required to maintain accuracy during an update, adding a layer of complexity to the embedded toolchain.

- Sparsity: Structured or unstructured sparsity (pruning) can drastically reduce the number of required computations, especially important when running an EWC-style update where the total number of updates is small. Hardware support for sparse matrix operations is becoming a core requirement for next-gen NPUs.

The Path Forward: Lifetime Learning as a Requirement

Catastrophic forgetting is the gatekeeper of long-lived Edge AI. To move beyond the static, brittle model deployed once, embedded engineers must adopt a mindset of Lifetime Learning. This involves:

- Adopting Hybrid Approaches: Combining the memory efficiency of a regularization method (like EWC) with the performance stability of a minimalist replay buffer (like Herding) offers the best balance of stability, plasticity, and low resource usage.

- Developing Observability: Deploying robust telemetry to detect novelty and performance drift in the field. The model should only trigger a CL update when the data distribution has measurably shifted beyond the safety margin, conserving power and flash endurance.

- Co-Designing Hardware: Pushing for NPUs and embedded memory architectures that natively support the unique memory and compute patterns of CL—specifically, high-speed, low-power writing for replay buffers and efficient support for matrix consolidation algorithms (FIM calculation).

The embedded AI system of the future won’t just be smart; it will be adaptable, capable of accumulating knowledge across years of deployment without forgetting its fundamental lessons. Overcoming catastrophic forgetting is not just an algorithmic pursuit; it is an exercise in rigorous, resource-aware engineering—the very definition of the embedded domain.

Connect with RunTime Recruitment

Are you an embedded engineer specializing in neural network optimization, resource-aware deployment, or low-power Continual Learning algorithms? The demand for talent capable of solving the stability-plasticity tradeoff on the edge has never been higher.

RunTime Recruitment connects elite embedded AI specialists with companies building the next generation of truly autonomous, long-lived devices. If your expertise lies in EWC, Rehearsal, Quantization, or NPU co-design, connect with us today to explore roles where your skills will define the future of Edge AI.