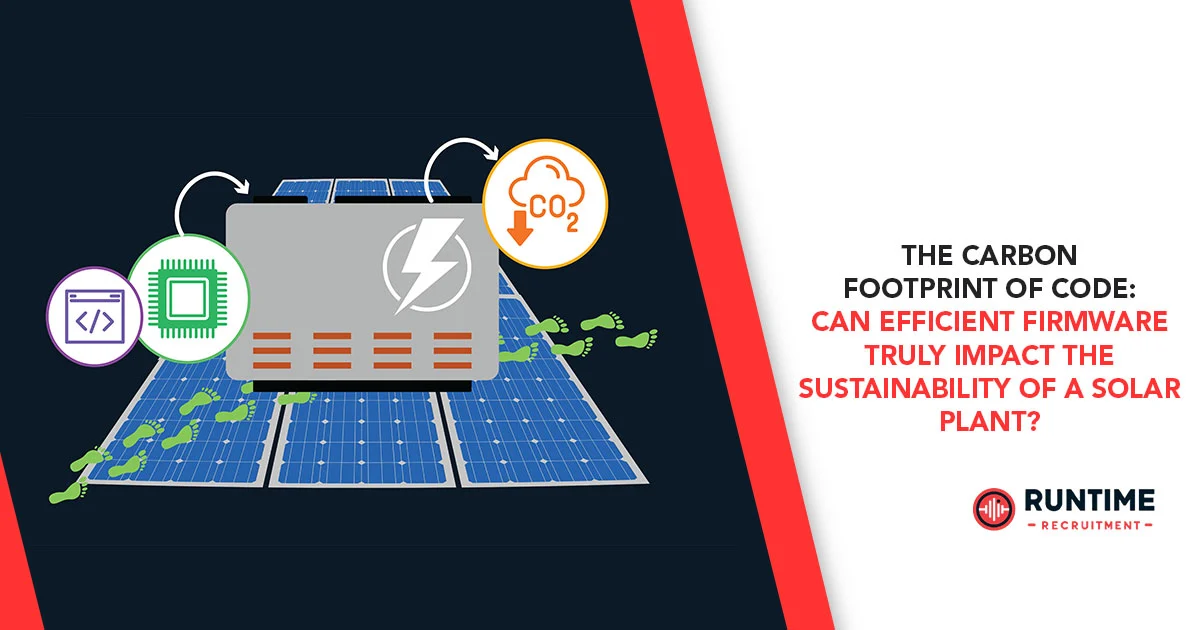

In the ongoing global race toward net-zero emissions, the spotlight is rightfully placed on large-scale, tangible infrastructure, electric vehicles, grid modernization, and, most prominently, solar power plants. These sprawling fields of photovoltaic (PV) panels represent humanity’s most powerful defense against climate change. However, beneath the gleaming silicon and aluminum, an often-overlooked component plays a critical, if minuscule, role in the overall equation: the embedded systems running the show. For the embedded engineer, this invisible layer of control, the firmware, is not just about functionality; it’s a silent contributor to, or detractor from, the plant’s ultimate sustainability.

This is the frontier of Green Software Engineering applied to the physical world. The question is sharp and urgent: Can the subtle, digital choices made at the keyboard truly impact the gargantuan, multi-megawatt operation of a solar power plant? The answer, as we will explore, is an emphatic yes, particularly when considering the vast scale, extended lifespan, and power-critical nature of renewable energy infrastructure. The concept moves beyond just “working code” to demand “conscious code.”

The Unseen Footprint: Understanding the Carbon Cost of Embedded Systems

Before we can address the impact of efficient firmware, we must first establish the concept of the carbon footprint of code. For enterprise software or cloud computing, this is often calculated through the massive energy consumption of data centers. For embedded systems—like those found in a solar inverter, Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) controller, or a weather monitoring station—the calculation shifts, but the principle remains.

Deconstructing the Embedded System’s LCA

The total environmental burden of an embedded system is assessed through a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), which breaks down the emissions into three primary phases:

- Embodied Carbon (Manufacturing): This is the carbon cost associated with the extraction of raw materials, manufacturing of the Microcontroller Unit (MCU), Printed Circuit Board (PCB), passive components, and the final assembly of the electronic control unit.

- Transportation and Disposal: The logistics of getting the unit to the solar plant and, eventually, its end-of-life disposal and recycling process (or, more commonly, e-waste).

- Operational Carbon (Usage): This is the direct energy consumption of the embedded system itself over its operational lifespan, powered by the electricity it consumes.

For a large-scale solar power plant, which is designed to operate for 25 to 30 years, the operational carbon footprint is the single most critical area where firmware optimization can make a direct, cumulative impact. While the embodied carbon of a single MCU is small, its energy consumption, when multiplied by hundreds of inverters and monitoring devices across a utility-scale plant for three decades, can become significant.

The Power of the Photon vs. the Draw of the Clock

Solar plants generate energy. It seems paradoxical that their control systems would consume a non-trivial amount of power. However, every solar inverter, every string combiner box monitor, and every sensor hub contains a microcontroller that is constantly drawing current. This is a parasitic load, energy that is not being converted for the grid or stored, but is instead being diverted to run the system’s own internal operations.

The power drawn by a typical 32-bit MCU in a high-performance run mode can be in the range of 20 mA to 50 mA (sometimes significantly more for high-end processors or radio-enabled devices) at its operating voltage. While this is a trickle compared to the power being managed by a multi-kilowatt inverter, consider the scale:

- A large-scale solar farm may have hundreds or even thousands of inverters, each with a central control unit.

- Numerous sensor nodes, data loggers, and optimizers are scattered across the array.

- The system operates 24/7/365 for 30 years.

Even an optimization that saves a fraction of a Watt per device, when multiplied across the entire fleet and extended over a quarter-century, translates into tens of megawatt-hours of total energy savings—energy that can now be sent to the grid, displacing fossil-fuel-generated power. In a clean-energy context, reducing the device’s self-consumption is effectively increasing the overall efficiency and net-positive impact of the plant.

The Engineer’s Arsenal: Firmware Strategies for Green Design

The embedded engineer is, therefore, a crucial player in the sustainability agenda. Their code is the blueprint for the system’s energy usage. Green Software Engineering principles, once applied to cloud and mobile, must now be rigorously applied to the firmware development lifecycle.

1. Algorithmic and Data Structure Efficiency

The most profound energy savings come from optimizing the fundamental logic of the application. An algorithm that executes in N clock cycles will consume less energy than one that requires N2 clock cycles, regardless of how efficiently the power-saving modes are utilized.

- Complexity Matters: Moving from a linear search to a binary search, or choosing a hash map over an array of lists for high-frequency lookups, can dramatically reduce the processing time required for critical functions like MPPT (Maximum Power Point Tracking). A faster MPPT algorithm spends less time searching for the peak power point, reducing the cumulative energy drain of the processor over the day, and more importantly, maximizing the power harvested from the panels.

- Data Footprint: Efficient data structures reduce the amount of memory access and cache thrashing. Every memory fetch is an energy expenditure. Using smaller data types where possible (e.g., uint8_t instead of int) and minimizing dynamic memory allocation (which can be computationally and memory-intensive) leads to a leaner, faster, and more energy-efficient execution path.

- Language Choice: While often dictated by the hardware, the choice of programming language has a measurable impact. Studies have shown that highly efficient, lower-level languages like C and C++ consume orders of magnitude less energy for a given task than interpreted languages like Python, making them the default choice for power-critical embedded systems.

2. Aggressive Power State Management

The single greatest technique for reducing operational carbon is to maximize the time the system spends in low-power sleep modes. In a solar plant, the system is rarely under maximum load, and much of its operation involves waiting for a scheduled task or an external interrupt.

- The Deep Sleep Imperative: The firmware’s main loop should be structured around putting the MCU into its deepest possible sleep mode (e.g., Deep Stop or Hibernate) for the longest possible duration. The adage should be: “If you’re not doing something critical, you’re sleeping.”

- Intelligent Wake-Up and Polling: Instead of continuously polling sensors (e.g., for temperature or voltage) which keeps the CPU active, the engineer should utilize hardware interrupts or timed wake-up intervals. For non-critical data, the polling rate can be dynamically adjusted, sampling every 60 seconds is far more efficient than every second.

- Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Scaling (DVFS): Modern MCUs allow the firmware to dynamically scale the operating voltage and clock frequency based on the current workload. If a task is not time-critical, the firmware should reduce the clock speed to the lowest frequency that satisfies the performance requirement, leading to a non-linear reduction in power consumption (power often scales quadratically with voltage). The MPPT loop might require full speed, but data logging can run at a fraction of the clock rate.

3. Peripheral Power Gating and Clock Gating

Microcontrollers are systems-on-a-chip, integrating many peripherals (UART, SPI, ADC, Timers, etc.). When a peripheral is not in use, its clock and power should be explicitly disabled via firmware controls (clock gating and power gating).

- Minimizing I/O: I/O operations, particularly flash and network communication, are highly energy-intensive. Firmware should buffer data and batch communication (e.g., uploading a log file once an hour rather than every minute) to allow the communication module to enter a deep sleep state for the maximum duration.

- Smart Sensor Control: Sensors should not be powered continuously. The firmware should only power up a sensor (via a dedicated control pin or FET switch) right before a reading, take the sample, and then power it down immediately. This is particularly crucial for power-hungry analog sensors.

Beyond Direct Consumption: Indirect Sustainability Impacts

The efficiency of firmware impacts sustainability in ways that go beyond the direct power consumption of the control unit. These indirect effects often have a greater overall impact on the plant’s environmental profile and return on investment (ROI).

1. Maximizing Energy Yield (The Primary Goal)

The most important function of the inverter’s firmware is to maximize the energy harvested from the PV array.

- Superior MPPT Implementation: Highly efficient, fast-converging MPPT algorithms, made possible by tight, optimized firmware, ensure that the panels operate at their true maximum power point even during rapid solar irradiance changes (like passing clouds). A 0.5% gain in MPPT efficiency translates directly into a 0.5% increase in the plant’s total energy output over its lifetime, displacing substantially more carbon than the control unit itself consumes.

- Grid and Plant Management: Advanced plant control firmware, optimized for low latency and high reliability, can better manage large-scale grid services, such as reactive power control and frequency support, making the integration of solar power into the grid more stable and effective. This contributes to a more reliable, lower-carbon grid overall.

2. Extending Hardware Lifespan (Reducing E-Waste)

Firmware, when properly designed, can significantly extend the operational life of the hardware it controls, directly reducing the e-waste footprint and the need for new embodied carbon expenditure.

- Thermal Management: Efficient code generates less heat. Less heat means less stress on the surrounding components (capacitors, power electronics), leading to a longer Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF) for the entire inverter. Firmware that intelligently controls cooling fans and manages power dissipation actively extends the device’s physical life.

- Over-The-Air (OTA) Updates: Modern, modular, and robust firmware designs allow for Over-The-Air (OTA) updates. This capability is paramount. It allows the plant operator to push bug fixes, security patches, and—crucially—efficiency improvements to deployed hardware. This prevents premature hardware obsolescence and avoids the “rip-and-replace” cycle, directly reducing e-waste and extending the payoff period for the embodied carbon.

3. Enabling Smarter Operations (Optimized Maintenance)

Sophisticated, resource-light firmware enables advanced diagnostics and remote monitoring.

- Predictive Maintenance: Optimized firmware can run complex diagnostic models on-device, logging high-resolution data and detecting subtle anomalies in system performance (e.g., a developing arc fault or a failing capacitor). By flagging potential issues before they cause a critical failure, the system allows for targeted, preventative maintenance. This avoids inefficient “truck rolls” (maintenance trips) and prevents catastrophic failures that would necessitate the replacement of entire, expensive hardware units.

📏 Measuring and Validating Green Firmware

The transition to conscious coding requires a new set of metrics. In traditional embedded engineering, the focus is on latency, memory usage, and CPU load. For Green Software Engineering, we must add Energy Consumption as a first-class metric.

Key Metrics for Energy Efficiency:

- Energy per Instruction/Operation: The total energy consumed by the MCU to execute a specific task or algorithm.

- System Quiescent Current: The minimum current drawn when the system is in its deepest allowed sleep mode. This should be minimized to ensure low-power operation overnight.

- Energy Payback Time (of the control unit): The amount of time the solar plant must operate to generate the equivalent amount of energy consumed by the inverter’s control unit over its full lifetime. Efficient firmware dramatically shortens this payback time.

Tools and Practices:

- External Power Monitoring: The gold standard involves using high-precision external equipment (like a digital power analyzer or a source measure unit) to measure the current draw of the embedded system in real-time under various operating conditions.

- Microcontroller-Specific Tools: Many chip vendors offer on-chip power monitoring tools or power-profiling modes that can be used during the development phase.

- Regression Testing: Energy consumption must be included in automated test suites. A new firmware commit should not only pass functional tests but also energy consumption budget tests. A PR that causes a 10% increase in average current draw should be flagged for refactoring just as surely as one that introduces a bug.

The Path Forward for Embedded Engineers

The promise of a solar plant is the elimination of carbon emissions, but this promise is slightly diminished by the necessary complexity of its control systems. The embedded engineer stands at a critical nexus. Their work on efficient firmware is not just a technical optimization; it’s an act of environmental stewardship.

The cumulative effect of optimizing the code running on thousands of controllers for decades is significant, both in reducing parasitic loads and in maximizing the net energy delivered to the grid. The Carbon Footprint of Code in renewable energy is real, and the highly specialized skills of embedded engineers, mastery of low-level languages, deep understanding of hardware-software co-design, and aggressive power management techniques, are precisely the skills needed to shrink that footprint to its absolute minimum.

This is a mandate for the next generation of industrial embedded systems. We must shift our mindset from “does the code work?” to “does the code work efficiently?” with efficiency being defined by energy and resource consumption. The solar revolution needs not just more sunlight, but smarter, cleaner code.

Are you an embedded engineer driven to work on high-impact sustainability projects, where every clock cycle and microampere matters?

Connect with RunTime Recruitment today to explore opportunities in Green Tech and renewable energy embedded systems.