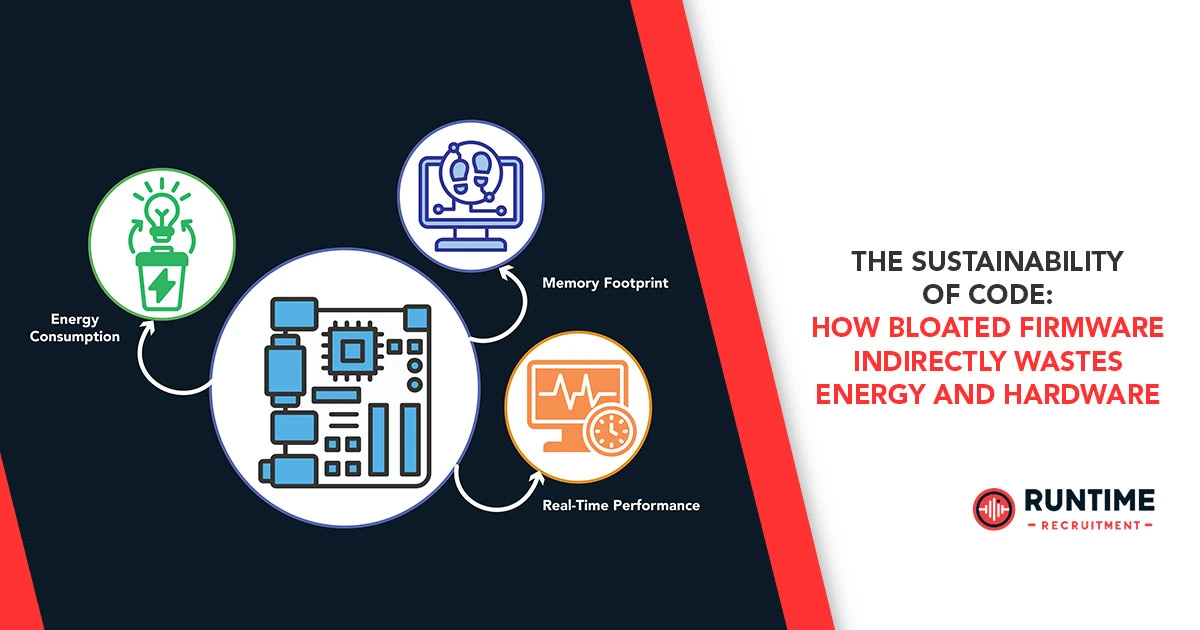

As embedded engineers, we are the architects of the physical world’s intelligence. From smart meters and medical devices to industrial controllers and autonomous vehicles, our firmware dictates the function, performance, and longevity of millions of devices. We are intimately familiar with the constraints of power consumption, memory footprint, and real-time performance. Yet, in the rush to market and the comfort of ever-cheaper, more powerful silicon, a insidious enemy has been creeping into our projects: software bloat.

This isn’t just about a few extra milliseconds of latency or a slightly larger binary; it’s a profound, systemic issue with direct implications for environmental sustainability. Bloated firmware, unnecessarily large, slow, or resource-intensive code, is a hidden drain on global energy resources and a driver of premature hardware obsolescence. This article explores the ripple effects of code bloat in embedded systems, dissecting how our pursuit of ‘good enough’ code inadvertently leads to a massive, indirect waste of energy and hardware across the entire product lifecycle.

The Hidden Cost of Code Bloat

Bloat, in the context of firmware, can be defined as the presence of code or data that consumes resources (Flash, RAM, CPU cycles) beyond what is functionally required for the target application. It’s often a result of feature creep, relying on heavy-handed libraries or frameworks meant for desktop environments, or simply sub-optimal coding practices that prioritize development speed over runtime efficiency.

The conventional view is that a few extra kilobytes of Flash or a slightly higher clock speed are negligible. When scaled across a product line of millions of units over a device’s typical 5 to 10-year lifespan, however, these small inefficiencies become an enormous, quantifiable liability. The sustainability impact of bloated firmware manifests in three primary domains: Energy Consumption, Hardware Over-Specification, and Premature E-Waste.

Energy Consumption: The Silent Power Drain

The most direct and measurable consequence of bloated firmware is its impact on energy consumption. In an embedded system, every unnecessary instruction executed, every superfluous memory access, and every extra clock cycle translates directly into wasted power.

1. Increased CPU Active Time

In most embedded and IoT applications, especially battery-powered ones, the primary energy-saving strategy is duty-cycling. The device wakes up from a deep sleep mode, performs its task, and returns to sleep as quickly as possible. The power consumed in the active state can be orders of magnitude higher than in the sleep state.

$$P_{total} \approx P_{active} \cdot \text{Duty Cycle} + P_{sleep} \cdot (1 – \text{Duty Cycle})$$

where:

- $P_{total}$ is the average power consumption.

- $P_{active}$ is the power consumed when the CPU is running.

- $P_{sleep}$ is the power consumed in sleep/standby mode.

- $\text{Duty Cycle}$ is the fraction of time the CPU is active.

Bloated firmware increases the active time. Inefficient algorithms, excessive function calls, or a verbose communications stack mean the CPU must run for a longer duration to complete the same task. If a highly optimized routine takes 50 milliseconds but a bloated one takes 150 milliseconds to process a sensor reading and transmit data, the latter consumes three times the energy for that task. When this is multiplied by millions of duty cycles over years, the collective energy waste is staggering.

2. Larger Memory Footprint and Access Power

Larger code size ($\text{Flash}$) and higher RAM usage (for data structures, stacks, and heaps) also directly increase power consumption.

- Flash Memory Power: Larger firmware necessitates larger Flash memory chips, which are more power-hungry both in terms of leakage current when idle and dynamic power during read operations. Furthermore, if the code size exceeds the capacity of cheaper, lower-power microcontrollers (MCUs), the design is forced to adopt a higher-end, more powerful, and inherently less efficient MCU.

- Cache and Bus Activity: Bloated code often exhibits poor spatial and temporal locality, leading to more cache misses. A cache miss forces the CPU to fetch instructions and data from slower, higher-power external memory (like SDRAM or external Flash). Each time the data bus is utilized for these lengthy transactions, dynamic power is consumed. A tighter, more efficient code structure ensures that instructions and data remain in the fast, low-power on-chip SRAM or L1 cache, significantly reducing energy spent on memory transfers.

3. Dynamic Voltage and Frequency Scaling (DVFS) Penalty

Some high-performance embedded systems use DVFS to dynamically adjust the clock frequency and supply voltage ($V_{DD}$) based on the workload. Since dynamic power is proportional to the square of the voltage and linearly to the frequency ($P \propto f \cdot V_{DD}^2$), small reductions in voltage lead to massive power savings.

Bloated, inefficient code may force the system to run at a higher-than-necessary fixed frequency or, through its increased execution time, prevent the system from aggressively dropping its frequency/voltage level as soon as possible. In essence, the performance overhead of code bloat prevents the optimal use of modern power-saving hardware features.

Hardware Over-Specification: The Need for Bigger Silicon

The most damning indirect impact of code bloat is how it dictates the underlying hardware specification. An engineer designing a new product must select a microcontroller (MCU) that can handle the maximum expected resource load. If the firmware is bloated, it directly inflates these requirements:

- Increased Flash/RAM: Bloat requires more on-chip Flash and RAM. This forces the design to move up the product stack to a more expensive, physically larger, and more power-hungry MCU package.

- Higher Clock Speed: If the application has a critical deadline (a real-time constraint), a bloated algorithm may fail to meet it on a lower-frequency, low-power MCU. The only design solution is to choose an MCU with a higher maximum clock frequency and greater processing power.

- Peripheral Inclusion: Bloated frameworks often bring in large standard libraries that assume the presence of certain high-power peripherals (like floating-point units or complex DMA controllers), even if the application only needs basic integer math. This forces the use of a more complex chip that includes these power-draining features.

This over-specification is an environmental disaster:

- Manufacturing Carbon Footprint: Manufacturing a higher-end MCU requires more raw materials (silicon, metals, plastics), more complex fabrication steps (e.g., smaller lithography nodes), and thus significantly more energy and carbon emissions during production. The “embodied energy” of a complex chip is substantial.

- Resource Depletion: It contributes to the faster depletion of critical, finite resources like rare-earth elements and conflict minerals.

- Cost and E-Waste: Designing for bloat increases the Bill of Materials (BOM) cost, potentially making the product commercially unviable or prematurely non-competitive. When the hardware inevitably fails or is decommissioned, the e-waste volume is larger and more resource-intensive to recycle.

By minimizing code size and execution time, engineers can reliably select the smallest, lowest-power MCU that meets the requirements, a concept known as “Right-Sizing” the hardware. This choice immediately shrinks the environmental footprint of the device’s production and operation.

Premature E-Waste and Obsolescence

A device’s sustainability is intrinsically linked to its lifespan. Bloated firmware can drastically shorten the useful life of a product, leading to unnecessary e-waste.

Feature Limitations and Update Failure

- Storage Exhaustion: A product launched with near-full Flash capacity due to code bloat has little to no room for future Over-The-Air (OTA) firmware updates. Critical security patches, bug fixes, or minor feature enhancements, all essential for long-term support and compliance, may become impossible to deploy. This forces the manufacturer to declare the device end-of-life prematurely, simply because the original firmware was not written with a resource-buffer for maintenance.

- Performance Degradation: Firmware updates, while sometimes fixing bloat, often introduce new, necessary features which add to the code base. If the original design was already barely performing on the selected hardware due to bloat, subsequent updates may push performance past an acceptable threshold, causing users to discard a perfectly functional piece of hardware because the software has become too slow (a phenomenon often called “software-induced obsolescence”).

Security and Maintenance Overheads

Bloated code is often complex code. Complexity is the enemy of security and maintainability. Larger codebases:

- Increase Attack Surface: More lines of code mean more potential bugs and security vulnerabilities. A massive codebase takes longer to audit and secure.

- Slow Down Debugging and Maintenance: Navigating and understanding an excessively large, non-modular codebase dramatically increases the time and cost required for maintenance. This friction often deters companies from supporting older hardware, again, accelerating the journey to the landfill.

The commitment to lean, modular, and efficient firmware is fundamentally a commitment to longevity and reparability, two pillars of a sustainable electronics economy.

The Embedded Engineer’s Call to Sustainable Code

The battle against firmware bloat is fought one commit at a time. As embedded engineers, we are uniquely positioned to champion code sustainability, turning our craft into a force for environmental responsibility. This requires a fundamental shift in our development mindset, moving away from ‘just get it done’ to ‘get it done efficiently.’

Principles of Lean Firmware Design

- Zero-Tolerance for Dead Code: Routinely use compiler and linker options (-ffunction-sections, -fdata-sections, –gc-sections) to ruthlessly eliminate unused code and data. Perform static analysis and functional testing to ensure that every byte of Flash serves a purpose.

- Right-Sizing Data Types: Avoid the lazy use of int or long when an int8_t or uint16_t will suffice. Selecting the smallest appropriate data type reduces RAM usage, minimizes bus transaction size, and improves execution speed on smaller architectures.

- Choose Libraries Wisely: The biggest source of bloat is often the unnecessary inclusion of large external libraries or frameworks. Instead of pulling in a massive JSON parsing library, consider a smaller, embedded-specific alternative, or write a minimal parser tailored to your specific payload structure. Understand the overhead of any library before integration.

- Optimal Algorithms and Data Structures: This is core engineering. A poorly chosen $O(N^2)$ sorting algorithm will consume exponentially more time and energy than an $O(N \log N)$ algorithm, especially on constrained hardware. Use profilers to identify and replace energy-hungry routines.

- Leverage Compiler Optimizations: Understand and strategically deploy compiler flags like -Os (optimize for size) and Link-Time Optimization (LTO), which can perform deep, cross-file optimizations the human eye cannot easily achieve.

- Static Memory Allocation: Favor static memory allocation over dynamic allocation (malloc/free) in real-time and deeply embedded systems. Dynamic allocation can introduce non-deterministic execution times, memory fragmentation, and code overhead, often contributing to bloat.

The industry is slowly shifting toward a “Green Software Engineering” ethos, but for embedded systems, where resource constraint is the norm, not the exception, this has always been our core mandate. We have a powerful advantage: our constraints are our guiding principles.

The Next Wave of Embedded Innovation is Green

The future of embedded systems is one of proliferation, billions of devices, each contributing to the global consumption of energy and materials. The cumulative effect of bloated firmware is a massive, unchecked externality that undermines the very concept of sustainable technology.

As leading-edge embedded engineers, our responsibility extends beyond function and performance; it now encompasses the environmental footprint of our code. By mastering the art of the lean binary, we are not just optimizing for speed or cost; we are engineering for a greener future. We are ensuring that the products we create are efficient, durable, maintainable, and do not unnecessarily accelerate the obsolescence cycle.

This shift in focus, from what the code does to how efficiently it does it, is the mark of a truly elite embedded professional.

Connect with RunTime Recruitment

Are you a seasoned embedded engineer committed to performance, efficiency, and code sustainability? Your skills in architecting lean, highly optimized firmware are in high demand by companies building the next generation of sustainable and resource-conscious products.

RunTime Recruitment specializes in connecting top-tier embedded talent with forward-thinking organizations that prioritize technical excellence and environmental responsibility. If you’re ready to put your optimization skills to work on challenging projects that truly matter, we want to hear from you.

Visit RunTime Recruitment’s website or connect with a specialist today to find your next mission in sustainable embedded engineering.